This story is part of Gen J, a new BBC Worklife series that spotlights Japan as the country heads into 2020. This is the third story in that series, looking at a societal expectation that even the youngest generation must be prepared to manage.

When you step on an escalator, do you stand to one side to let others pass? When someone in the room says it’s hot, do you open a window? If you ask someone on a date and they stare at you blankly, do you withdraw the invitation?

If you don’t do any of these things, some unfortunate news: you cannot “read the air”.

Knowing the unspoken rules governing social life requires comprehensive understanding of your environment, whatever the setting. It’s a skill that’s valuable anywhere in the world – but in Japan, where communication tends to be indirect, it is elevated to another level. Reading the air – kuuki o yomu in Japanese – is a constant exercise, and misreading the air can blow business deals or ruin relationships.

In Japan, kuuki o yomu is grappled with in everything from facial recognition technology to video games, showing how ingrained it is in daily life.

Part of this is thinking in the shoes of somebody else – Shinobu Kitayama

Reading the room

Last year, a tweet went viral in Japan; a businessman in Kyoto met a potential client, and after a while the client complimented the businessman on his watch. At first, the man started to explain the watch’s features – but then realised that what the client really wanted was for him to look at his watch, see what time it was and wrap up the conversation.

Rochelle Kopp, who runs cross-cultural training firm Japan Intercultural Consulting, says that while all nations have varying degrees of indirect communication, in Japan the phenomenon is more prominent in society. “In other words, in Japan, it is especially important – and you can expect more problems if you are unable to do it. Put another way, it’s an important societal expectation,” she says.

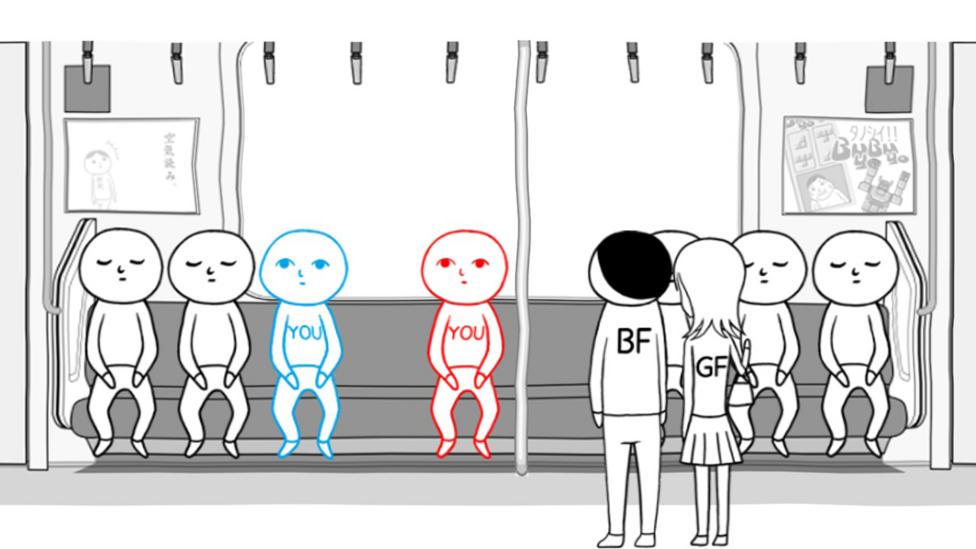

Kuukiyomi: Consider It is a video game all about reading the air, which was recently translated into other languages for international release (Credit: G-Mode Corporation)

Yoko Hasegawa, a Japanese language professor at the University of California, Berkeley, says reading the air requires diverse knowledge – cultural and historical, as well as inside knowledge of those in the dialogue. When two people “are praising each other, it might be the case that they are arch-enemies. If you can’t read this ‘air’, you might say something that inflames the hostile relationship,” she explains. “Because my knowledge is frequently inadequate, I can’t read the air in social gatherings [here] in the US.”

In Japan, for example, if you’re the person speaking loudly in an otherwise silent train car or talking to a client who has long since lost interest, you risk being labeled KY – a pejorative Japanese slang term that stands for “kuuki ga yomenai”, or “unable to read the air”.

“Every group has a few people who are labeled as KY,” says Shinobu Kitayama, editor for the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology and professor at the University of Michigan in the US. “Often times, you’ll be kicked out from important discussions in many organisations. And sometimes, that can be part of the reason for school bullying. If you find [reading the air] stressful, that’s a problem.”

Mastering micro expressions

A big part of “reading the air” is picking up on non-verbal cues. David Matsumoto, a psychology professor at San Francisco State University who specialises in cross-cultural and non-verbal communication, studies micro expressions: tiny involuntary facial tics that can give away a person’s true emotions.

When, for example, a client at work says they’re happy with the job you’re doing, a very subtle lip twitch or eyebrow raise could mean they’re fudging the truth. Noticing micro expressions, along with other non-verbal communication, is important in any interaction, no matter where you are.

“Silence is one non-verbal cue. Shifting of posture is a non-verbal cue. A social smile could be another cue,” says Matsumoto. “All of these are part of the non-verbal package that contribute to that contextual meaning.”

It definitely forces you to pay attention, and to think about what signals the people around you are putting out – Rochelle Kopp

Matsumoto runs Humintell, a company that provides workshops on how to get better at deciphering micro expressions and other non-verbal signals. Others provide such services, too; in Tokyo’s Toranomon business district, researcher Kenji Shimizu runs the Institute for Science and Being Sensitive to the Situation.

Like Matsumoto, Shimizu teaches people – mostly Japanese businesses or government agencies – how to master micro expressions. Shimizu uses a system developed by US psychologist Paul Ekman, who coined the term and describes the subtle facial changes as “involuntary emotional leakage”.

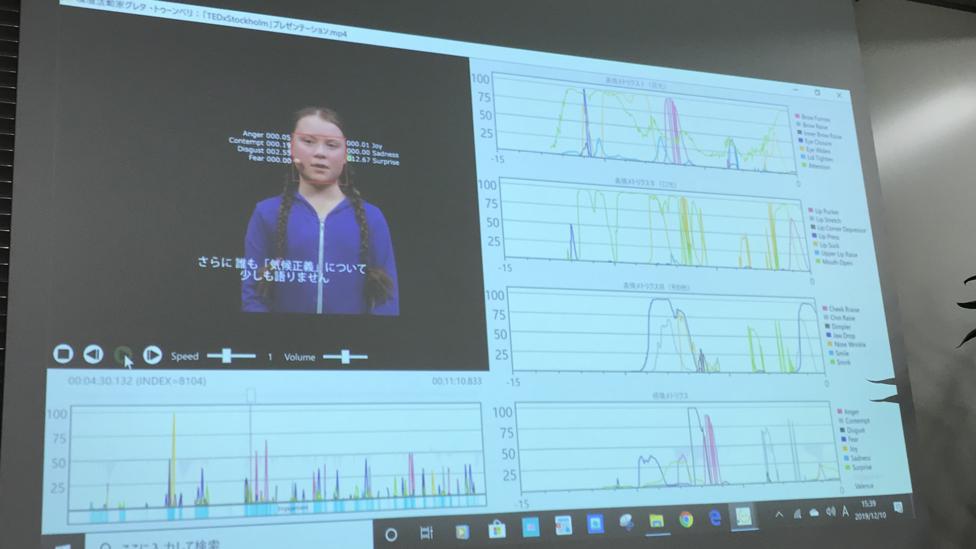

Shimizu uses visual materials to show clients what to look for, like this interview with New York Yankees player Alex Rodriguez in 2007 when he lied about using performance-enhancing drugs (watch for the twitch at the side of his mouth). He sometimes employs software that uses a laptop camera to track seven basic human emotions on a person’s face in real time, to help them better understand the signals they’re sending out.

“If you notice someone’s disgust – wrinkling around the nose – or anger – brows lowering, eyes widening, lips pressing – [and yet those expressions are] masked by smiles, you can consider their wishes,” Shimizu says, “and ask them what they really want you to do.”

Kenji Shimizu is a researcher based in Tokyo who helps people get better at reading body language to pick up on hidden messages (Credit: Bryan Lufkin)

Gaming the system

Still, deciphering body language is just one part of the much larger skill that is reading the air. It’s also about knowing the context of a situation. That’s especially important in a “high-context” country like Japan – where messages are not always spoken, but instead implied and must be inferred.

Reading the air is so entrenched in Japanese culture that there’s even a video game about it. Last month, Kuukiyomi: Consider It was released for Nintendo Switch. Players are put in over 100 delicate situations and scored on how well they read the air. In one scenario, you’re sitting on a train with an empty seat next to you and a couple get on. What do you do? If you read the air, you stand up so both can sit together.

It’s a chance to hone your skills – or rebel against the status quo. And in a country that runs on reading the air, that might be welcome relief, says developer Koichi Takeshita. “Most [Japanese] players enjoy not reading the air purposely in this game,” he comments.

Nonverbal communication is just one part of reading the air, but there’s software that tracks facial movements to train people to improve in that area (Credit: Bryan Lufkin)

Improve your reading

So how can you get better at reading the air – especially if you’re lacking key cultural or insider knowledge?

“Part of this is thinking in the shoes of somebody else,” Kitayama says. Even when it feels stressful, rest assured: “You can cultivate those skills.” Sometimes practice makes perfect; Hasegawa recommends “trial and error through socialisation” and to “cultivate the desire to behave like others”.

Kopp says it’s hard to train people on, but she simply “urges them to keep their antennae out”, pay attention to those non-verbal signals and proactively ask questions about what will be expected in a certain situation.

Having even a little cultural knowledge can help you figure out what to do next, adds Matsumoto, whether you’re looking at someone’s face or reading the room. “It comes down to some really basic things, like being respectful of the other culture, and be interested. If you’re interested, that will help you listen better and be an active listener, and also active observer,” he says.

“[Kuuki o yomu] definitely forces you to pay attention, and to think about what signals the people around you are putting out,” says Kopp. “That is indeed a good habit for any businessperson to have, no matter what the situation.”

This article first appeared on bbc.com